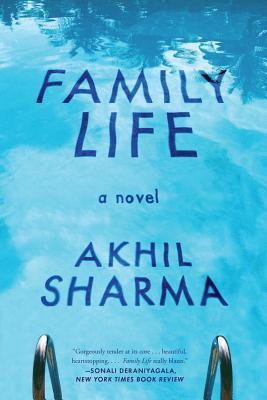

Family Life Akhil Sharma

How do you even begin to write about a book that is so painfully honest that it can be tender and heartbreaking in the same sentence. In its most mundane parts. This is the story of Ajay growing up envying his older brother, Birju, in every sense of the word. Once when visiting their grandparents Birju is the one to inform them that their father has sent tickets for the family to emigrate to America. Immediately Ajay is in a state of resentment for not having been the ‘bearer’ of this good news. Everything Birju does seems flawless and infinitely wise to Ajay. But an event that renders Birju entirely disabled changes their lives forever. It’s comforting to put the book in that box - to call it a story of loss and dealing with that loss, but it turns out to be so much more.

The plot here is simply of time passing. We grow with Ajay and his thoughts. Living with a person with a disability is a full-time job in many cases, one that we don’t automatically realize. But what happens when that person is your older brother who you used to envy? What happens when everything you ever wanted – to be the wiser, cooler, more successful brother – suddenly come to fruition at a cost you could never imagine? This is as much a coming-of-age story as it is about the burden of responsibility, about what we do for the ones we love. There’s a few parts where Ajay talks to God (he’s conversing with himself) and we learn that love is not always about blind devotion. That we all have to find our way back to it constantly.

“I’m ashamed,” I said.

“About what?”

“That after the accident, I was glad I might become an only child.”

“Everybody thinks strange thoughts,” God said. “It doesn’t matter if you think something.”

“When I was walking around in the schoolyard and you asked if I would switch places with Birju, I thought, No.”

There is a constant underlying guilt that Ajay – the narrator – lives with as he grows with his brother, trying to learn how to love him again. It is so painfully honest. I’ve often wondered where this capacity to love endlessly come from - where one spends their days caring for their own without any expectation of reward or return. Surely there is a sense of duty here, but in that duty, is there always some form of love?

Akhil Sharma puts it succinctly through Ajay’s lens (and often the other family members who are equally battling their own demons). We find the boy often asking himself why things aren’t just normal in his life. Anyone who has spent caring for the disabled, the mentally ill, or even their very old grandparents knows this feeling of wanting to not care for a little while. But we don’t like acknowledging this thought, for it is a duty, and acknowledging it would render us weak. We see this time and again in this autobiographical novel - the clash between love and duty on the one hand and on the other the desire to simply walk away from it all.

Unlike most novels that deal with some kind of loss or grief, this isn’t some earth-shattering story. This is the sharp pain of a needle-stab that you only feel when it’s slowly being extricated. That feeling is already inside all of us, Family Life just manages to make its presence known. It showed me that one can live with loss and it doesn’t have to be perfect. It doesn’t require perfect composition and unconditional love or even eternal devotion. It requires that we come together and strengthen each other when the road gets rocky. It requires that we put aside our ‘strange thoughts’ and find ways to love again. It shows that love has to be cultivated, and not found.

When I think about loss, it’s usually about death. I read Wave, where Deraniyagala lost her whole family, and I thought this is what loss is about. But what struck me is that the disability that Birju has is an even more profound kind of loss. He’s there, and he’s alive, but he’s practically in coma and now you have to care for him for the rest of your life. (There’s even a point where the mother describes his state as being in a coma, because simply saying he’s brain-damaged doesn’t elicit as much sympathy in others.) Disability can, at times, be a greater pain to deal with than anything else and we all ought to do more and do better to acknowledge and understand this.

But this is not all about grief and loss. There are tender moments of communities helping each other out, of acceptance of our fragile selves, of growing teenagers exploring love, and what it means to be vulnerable. I wanted to pick out a few quotes from this book that show this aspect that despite all odds we still do the routine things - we still want to love and be loved, we still want to find success, and we still oscillate between wanting to be better and wanting to give up. But it’s nearly impossible since there are so many little moments like these that I eventually stopped marking them. They are the real gems of this book.

A phone call cost ten cents a minute if made after nine o’clock at night. To save money, we spoke every other day. On the days we didn’t, I would call her room at nine and hang up after one ring. She would then do the same, and this was how we said we loved each other.

Pick it up if you can. This is a book for the shelf.